In early September, last year, I participated in the most inspiring, courageous and progressive event I have ever been a part of during my whole activist life. This event was the first LGBTI Pride March in Bosnia & Herzegovina.

My presence in Sarajevo was only the second time I had marched for LGBTI rights in the Western Balkans. Before then it was in Podgorica, and subsequently in the inaugural Dyke March in Tirana. They were also the first pride marches for me where violence or attacks were a real possibility. I was out of my comfort zone.

Why, I hear you ask, would you want to go? Well, on the activist side, I am a member of Rainbow Rose, a social democrat LGBTI campaign and advocacy group, which seeks to further LGBTI rights across Europe. My task is to focus this work on the Western Balkans, working with our Party of European Socialist sister parties and LGBTI NGOs to achieve that. On a personal level, I am privileged to have come out and grown up in the UK during a time of fundamental social and political change concerning LGBTI rights. Activists before me, from the 1950s onwards, had put the case for change forward, and marched in their thousands so that people like me can be seen and counted. I wanted to support my LGBTI community in a country that pressures them into hiding their identity.

So, with Rainbow Rose, I organised a small delegation to support the organisers of the first pride. For four days I would be in Sarajevo, meeting with SDP BiH members and NGO activists, and participating in the march.

However, my initial apprehension about visiting Sarajevo and being explicitly ‘gay’ was first tested during my flight. I had taken a now familiar route whereby I had to transfer in Vienna. On this occasion, unlike earlier in the year, I had time to switch flights in less of a rush. I sat by the window next to a married couple in their 50s. I glanced over as they were both looking at the wife’s phone. It was a post on Facebook that they were looking at. It showed a mathematical equation containing screws and nuts. A screw and a screw equalled a big red cross. The same result was given for two nuts together. However, a big green tick was the result when a screw and a nut were added together. The couple chuckled at the message it promoted.

I do not know whether they laughed because they agreed with its message, or because of the absurdity of the picture and its meaning, but I felt very uncomfortable sat next to them for the next hour. I made sure not to play any film or programme on my laptop with an LGBTI theme, nor take out my paperwork for the visit. Neither did I challenge them. I didn’t want my cherished opinion of Sarajevo to be dinted by any anti-LGBTI sentiment or aggression.

So, it was with these emotions that I disembarked the plane and left the airport. A sweeping and crashing thunderstorm that roared overhead, a mere 15 minutes after landing, was somewhat ominous.

However, my perception and expectations ahead of the march began to take a turn for the better. That evening, I read up that we may have to call at a police station to register our stay. As we were heading out anyway, we found one local station and went in. A few police officers were heading out, and a couple were in a side room having a conversation, guns and batons clipped to their sides. I gesticulated that we needed attention, and an officer came out. I started speaking English, so he called over a colleague. I explained that were in an apartment for a few days, and that we had come to register our stay. He looked a little bemused and rhetorically asked that if we were wanting to the pay the city tax, then offered that we didn’t have to. Caught a little off guard, I continued that we were just here until Monday and that I read we needed to register. It was at this point, and out of nowhere, he said in a functional manner “Are you here for the march?”. I must have immediately blushed, but Joseph who I was with, with almost precise comedy timing and a hue of innocence, said “What?”. The officer, perhaps blushing himself for speaking out of turn, said “Let me see your passports” and rather quickly said we did not need to register, and hoped we had a pleasant trip. All I could do was scream in relief once we reached around the corner of the building.

Yet, despite my own fear of being ‘outed’ in a police station and presuming things may have taken a sour turn, this was a small acknowledgement that the march had indeed seeped in to the public consciousness; even if it was only because this officer would be patrolling the march. The next day, another small incident allowed me to move towards cautious optimism for the march.

Once my core delegation was complete, with Jose arriving the following day, we decided to take a trip up Trebević, the location of the 1984 Winter Olympic bobsled course. A steep walk to the base station, led to a very enjoyable ride on the newly re-opened cable car system with incredible views. There were a number of fellow tourists, but not overbearing. We walked along the old bobsled track, with its abundance of graffiti. As the four of us walked along, Jose and Joseph spoke in Spanish. It was during this conversation that one guy in a group of three interjected as he walked past. He was curious as to where my friends came from, and they had a brief conversation about Spain. The conclusion to this was that the passer-by asked if we would be attending the pride march tomorrow. My heart sank, accepting that in all of the places, we would have to be called out for being gay on a quiet mountain side. Jose almost flirtingly replied “Of course”, and with that came a positive acknowledgement from the guy that he would see us there. Amazing.

Another small, whispered comment was made to Jose once we left a restaurant the day before the march. During the dinner, Julie Ward, former Labour MEP for the North West of England, regaled to us her story of getting a taxi from Sarajevo airport to her hotel, where she candidly told the driver that she was here for the march. His reply was one of enthusiasm, and a discussion ensued of the benefits of the march. After eating, as we departed, one of the waiters caught Jose and said “Good luck for tomorrow”. At a bar later on, where we met other social democrats who had come to march, one of them overheard locals discussing the march tomorrow. I asked in what way were they discussing it, positively or negatively. He said more ‘matter of fact-ly’.

Evidently, this was a much talked about event and one that hadn’t rallied the mass opposition that some of their number had hoped. There was a rally a few days before the march, where the religious participants, rather foolishly, used balloons in the colour of the Trans flag to try and make a point about boys, girls and families being harmed by such a display of queerness. Another protest was planned on the day itself.

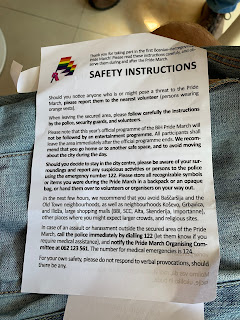

Sunday had arrived, and there was a sense of occasion about the main event. We followed the strict directions, as agreed by the pride organisers and police, as to where we needed to enter and what we were allowed to bring in. The police operation was firm but very professional – at the start and throughout. Those familiar with Sarajevo will know how one minute you are walking down tightknit roads and side streets, hidden by the towering 18th century buildings in this part of town; only to then be on an open plaza or river embankment in full view of the hillsides. We met our fuller delegation in the square in front of the Sarajevo Youth Theatre, to have a coffee and do formal photos of our attendance.

I watched as people funnelled through security, a few not heeding the warning to not wear LGBTI regalia until through security. Many were in groups, but others came as couples or by themselves. Many were evidently heterosexual, which was heartening to see. But once through security, the colours began to bloom. On flags and banners, on t-shirts, on people’s faces with paint or glitter. Where we were, we could hear the thud of drums not too far away, and the echo of a voice on a loudhailer. On the square where we were, the sound of whoops and squeals reverberated every time a planned rendezvous had been accomplished.

We then made our way to the main street, a minute’s walk away. The security cordon stretched between the Eternal Flame Memorial and the Central Bank, on the main westbound road from the Old Town called ‘Marshal Tito’. We turned the corner and saw a sizeable gathering that must have numbered over the expected turnout of a thousand already. We were 45 minutes away from the start. I managed to say a hello to a few activists I knew, before finding a spot to situate ourselves. Someone asked if I could say a piece to camera to say why I was here, and why it was important. I duly obliged.

As more people began to fill our space, the atmosphere became electric. Drums were banging, whistles were blowing, and a wave of chanting flowed over the crowd. Rainbow flags were furiously brandished, and placards with an array of messages were jumping up and down overhead. The crowd was well over two thousand by now.

And then all of a sudden, with a cacophony of whoops and wails, we were off. And it couldn’t have been more peaceful, felt more liberating, nor garnered as much positive support than if you wished it. At first, there were no passers-by on the street along which we walked, but you could see faces in the windows of the apartments above. Only the odd face here and there, expressing curiosity. But then I noticed a young family, outside on the balcony, and they were waving. We then approached a modern mall, which had a roof terrace. It was packed with people watching. But that was it; neither cheering or heckling. Just observing. The crowd waived cheerily at them.

And as we went along, we kept seeing more faces in windows, and then people waving back. The scene that was often repeated, and which I got real emotion from, was seeing older women in their 60s and 70s, waving and clapping alone from their windows. What I took from that, and this is only a theoretical proposition with no anecdotal evidence, was they were expressing nostalgia for a time when everyone was equal, and understood having lives with and through hardship. I took their support to be one of compassion and understanding. It was just a feeling, but one that carried me all the way along the march.

We walked past aging mosques, the Presidential Office, many a war-torn building, but never any hatred. The only signs of dissent were the appearance of buses used to block the main roads into the city that crossed our route. And even then, you couldn’t see protestors. As we approached the Parliament area, a raucous cheer went up, as people in front of us turned 90 degrees to the right to look back at something. As I reached that point, I saw an elegantly dressed woman in her 70s or 80s, in a ground floor window. She had jet black hair, a black top and a large white beaded necklace. She was blowing kisses to us all. My heart lifted.

Meanwhile, as I was marching, I made a comment about someone’s t-shirt that had a sheep on it and mentioned Wales. Two women in their 50s next to me exclaimed “We’ve been to Wales!”. It turned out; they were from Sarajevo and had studied in Aberystwyth University for a number of years. We had a lovely chat about the film Pride.

The march then poured into an area where the two main roads merged, and opened out to a large expanse where the Parliament was situated. Those familiar with the siege of Sarajevo will recall many a photo or video footage of people hiding or running across this area, under the threat of sniper fire. I felt our presence now was also an act of reclaiming this space from the past. Opposite the parliament building on two sides were modern shopping malls. The terraces were again packed with observers.

The pride organisers stood upon some steps and made proclamatory speeches. My colleague, Dajana Bakic, started off proceedings. This was followed by a local artist singing two songs. One, I was told, was a Yugoslav anti-fascist song, which the crowd sung with gusto. The other was Bella Ciao, the Italian peasant song turned revolutionary anthem. Overall, the blend of LGBTI and anti-fascism proved a dynamic match, rousing a nostalgic call to arms akin to ‘Brotherhood and Unity’ but for modern times.

As proceedings ended, people sought friends who they missed during the march and caught up. Others were reeling from the high of the first LGBTI march in Bosnia & Herzegovina. Many were invited to a reception in the nearby Museum, our delegation included. This was set up to ensure a safe space following the march, should protestors try and attack people as they left. Buses were parked nearby for those to travel home, if they came from places like Banja Luka or Belgrade. At the museum, we met acquaintances old and new, and chatted with the Spanish and British Ambassadors, who were very pleasant indeed. A thunderstorm left as quickly as it arrived, but brought the reception to a natural end. Our delegation went its separate ways, but those staying for another day returned to the apartment.

That evening, we reunited with our friend from the bobsled track on Trebević, as we were invited to a house party hosted by his friend. The evening was spent making new friends and drinking copious amounts of homemade rakija. The next day, we visited the grocery shop downstairs. In the magazine racks, I noticed one publication that had a rainbow flag on it. Inside was a 4-page article on LGBTI pride, with pictures taken of that summer’s Europride in Vienna. The magazine happened to be the most popular women’s weekly magazine in Bosnia & Herzegovina. No wonder public awareness was so high.

And so, that was my pride in Sarajevo. My departure was filled with a lot more optimism than when I arrived, and it taught me an important lesson. Don’t just count those who show opposition, and then let that skew your judgement and preconceptions of a place or people. Allow for the positive shows of support to boost your hopes for the event, and indeed the future. Also, don’t discount those who show indifference as being negative by default. The law of averages would indicate that they are neither agitated nor motivated – it’s just not a priority for them.

Until the next Bosnia & Herzegovina Pride!