We decided to have breakfast in the

apartment this morning, no doubt because of the effect our vodka and wine

induced evening had on our reluctance to venture outside so early and in such

searing heat. So coffee and (non fresh) chocolate croissants it was, before

showering and packing for the day. Today the sky was pristine – not a cloud.

Hence we packed sun cream, factor 50 naturally, and lots of water. We also

packed ham and bread so that we could have a picnic later in the day. But first

we had a task to complete.

We left the apartment, on to the main

square, and then turned right aiming for the naff Arc de Triomphe replica. The

only saving grace in my eyes were the remnants of the colourful revolution,

etched on to the monument as a reminder of another triumph the citizens were

seeking to achieve. Onwards from this the 11th October Street merged

with a road from the right, its name a symbol of the start of the Partisan resistance

in 1941 commemorated by the Communists. And as we walked on, symbolism from the

current era was evident everywhere. To our left was a park, adjacent to the

brutalist mall, which contained almost a graveyard of religious, cultural, and

event-marking structures. The first to appear involved Greco-Roman men linked

arm in arm, with the world being held behind them. The dates and list of names

pointed towards this being a memorial to the Macedonian security services that

were killed during a low level insurrection in 2001. Initially a localized

skirmish, involving a transfer of land between Macedonia and what was then

Serbia, escalated into an ethnic conflict. No Albanian names could be seen.

A peppering of statues that had no explicit

symbolic reference led us to the end of the park. Here, a latterly installed

statue heralded the first meeting of the Macedonian ASNOM in 1944 – the

Anti-fascist council that was led by Tito prior to the war’s end. Kiro

Gligorov, the first post independence President of Macedonia, sits prominently

at the table whilst a comrade speaks from the lectern. The Government seemingly

had to mix it up a bit with a statue from the Communist past. It was noticeable

that there was still no Albanian statue this side of the Vardar. Opposite the

park stood the Macedonian unicameral Parliament. Even it didn’t escape the

‘make-over’ of the city, with tacky domes forced onto its wings and cream

paneling covering its original terracotta marble effect facade. For fear of

under doing it, another man on a horse was placed outside.

After our little tour of ‘Disneyland’ we

walked on. Even after only leaving the apartment 10 minutes earlier, the heat

was overpowering. We took a left

at the junction and walked back towards the river, turning right at another

small modern shopping mall. We picked up a fellow traveler on the way – a stray

dog. What was a cute addition for a few minutes soon turned into an annoyance

we couldn’t shift. The dog became aggressive towards certain passersby and

fellow stray dogs. I felt both lucky to have the dog ‘on our side’ but

impatient for it to lose interest in us and wonder off. However it was with us

all the way to the dilapidated rail and bus station. Built following the

earthquake, there was a hubbub of activity at its entrance, consisting mainly

of taxi drivers and food vendors chatting amicably whilst eyeing up potential

custom. We walked straight in, past the row of bus company desks to our left

and a waiting area to our right, through to the other side of the station. We

could not find the train station area. Outside now, we turned left towards the

road, then under the bridge that supported the rail platforms. We found a secretive

side entrance into the dark and unwelcoming train station hall. No one was

about, and only one desk was staffed. In English, I asked if there was a day

train to Belgrade. We were informed that there was not, only a night train. I

was really disappointed, as I wanted to see the countryside slowly pass by as

we took our first train journey. We left the desk and considered our options.

We decided to ask at the bus desk for times of departures and cost. They had a

couple of ‘express’ buses that only departed at nighttime and took 6 hours, and

other buses departing during the day that took around 8 hours. We decided

against night travel so opted for one of the day buses. It cost the same amount

we budgeted for the train, so we weren’t dipping into reserves. We paid for our

tickets, and I left reassured that our transport to Belgrade was now confirmed.

With our task complete, we walked back to

the Ramstore, our canine friend nowhere to be seen. Whilst walking over we

agreed that our next visit should be the cross on top of Mount Vodno. I was

eager to go following my aborted attempt the last time I visited. So at the Ramstore,

we jumped into a taxi and made our way up the windy road to the cable car. Our

taxi driver was a woman in her mid-50s. She spoke good but broken English and

was very chatty during our drive. She explained to us, somewhat nostalgically,

that when she was in school, they had a choice of languages to learn and she

chose English as it was one of the most common ones. She was interested to hear

that we planned on visiting Matkasee, so much so that she gave us her number so

that she could take us there tomorrow. We took her business card as we departed

and waved her off.

We walked along a path with a shop in a

wooden hut and picnic benches dotted within the ascending forest to our left.

John was very impressed with the free wifi available in such a remote place.

Very ‘back to nature’ I thought. We walked on to a ticket booth and the lower

station of the cable car. We paid

our £4 fee and boarded our private pod. We slowly slid up the side of the

mountain, and as the trees departed we could see the city below us. At first,

it was the entirety of our view, but as we climbed the whole valley came into

range. Villages that emerged on the horizon soon came to be viewed from a

Birdseye perspective. As we neared

the top you could see the crescent shaped valley from east to west, with the

mountains to the north our only obstacle to peering into Kosovo. We arrived at

the summit and departed our pod. The Millennium Cross stood stoically ahead of

us, and to its right a run down restaurant that seemed closed for

refurbishment. We visited the small kiosk in its base to buy snacks, and then

decamped on to a table to eat our picnic whilst soaking up the views.

The 360-degree panoramic view was truly

awesome. The clear day meant you could even see Serbia over to the east,

towards the end of the mountain range. To the west emerged a motorway out of

the city, partly taking form as a lengthy viaduct heading towards Tetovo, the

predominantly Albanian town. After our picnic, we had a wonder along the

mountain ridge. There were open circular wooden huts dotted across the

mountaintop, only about 5 or 6. One was occupied with an amorous young straight

couple. We walked along to the furthest hut, then back again, and on to a run

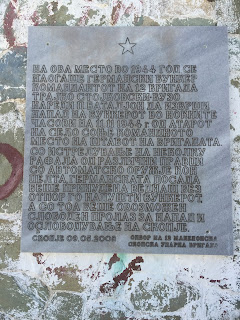

down building that had a plaque marking a German Command Bunker – prime spot if

any. We saw a workman in his 70’s emerge from a nearby building site and walk

down the hill and into the thick forest just below. We took a few more pictures

and then decided to make our way back down, waiting to avoid another group so

we had a pod to ourselves again.

We reached the lower station, and walked

over to the car park. There were no waiting taxis so we decided to use our

phones (without 3G) to descend the mountain via the forest. We saw a large map

on a billboard next to a large hotel-like building just off the roadside as we

left the car park, but the colour coding was undecipherable. We could see from

Google Maps a track through the forest, so decided to go for it. As we got off to a false start, we noticed the workman from earlier. He was obviously heading

home on foot. We saw him dip into a slender gap in the forest on the side of

the road, so we decided to follow him. He could have been anyone, but we

decided to trust the stranger rather than our own technology and sense. Though

as we descended, we saw coloured markings on trees every so often. It finally

twigged, about half way down, that three different colors direct you in three

different ways. I believe we took the easy route. After 45 minutes of walking

on a dry dirt track, we came across man made works embedded in the forest –

some form of water drainage system for the mountain – then re-entered

civilization with a farm or two, then houses with grand gardens.

We passed a shop as we walked down hill

in the up-market, hillside neighbourhood and grabbed a couple of iced teas and extra

water, before heading to a café I researched before arriving. The downside of

Macedonia is that it has a terrible record on LGBT rights. There is one LGBT

resource centre that in the past has been attacked on a number of occasions;

and the Dutch Embassy has done a lot to support civil society to make the LGBT

community more visible, acting as a symbol of hope. However, I managed to

research somewhere that was LGBT ‘friendly’. It was west of the main square 10 minutes

on foot, tucked in a cul-de-sac just off one of the main boulevards. It had a

bohemian pop-up vibe about it. There was an entrance gap between high walls

either side, and in the middle of the courtyard stood a large tree, in a rather

parched pond, with wooden seating constructed over and around it. We were the

only patrons. Our thirst not even quenched by the iced tea and water, such a

hot day that it was, we asked the waitress for a drink and was suggested a

local specialty. I accepted and was offered basically an iced tea. Oh well. We

sat in the shade for about half an hour whilst we regained energy and hydrated.

The café leant against a 4 story high residential block, where we got our free

wifi from, and was sheltered under the tree and a tarpaulin canopy. Upon

leaving, we noticed a military truck parked nearby and a few officers. My

suspicions were roused – was this place being watched? Was it really an LGBT

friendly place or a trap to lure us in? More realistically, it was probably

parked at the back of a barracks. We crept back out on the boulevard, lest we became

associated with the ‘friendly’ venue.

The sun was starting to lower in the sky,

so that the larger buildings were providing much appreciated shade from the

heat every so often. After a long and busy day, we returned to the apartment

for a snooze and refresh. By around 9pm, we woke up, got showered and changed

again, then sat on the balcony drinking some red wine, recanting our day thus

far and plans for tomorrow, whilst simultaneously observing the hubbub below.

The screaming lady returned once more. After draining much of the bottle, we

had to remind ourselves that we were intending to go out, so we locked up and

went down to the Square. Tonight we decided to go to one of the restaurants

along the riverside. The bridge looked amazing lit up in the night, with the

byzantine museum and theatre looming grandiosely behind. Again, the square was

busy with families and couples. We walked by the restaurants, checking out

their menus, until we decided on a place that looked quite classy called ‘Carpe

Diem’. We sat in the canopied section outside, eager again to observe Skopjians

going about their evening. We had a full, three-course meal (John may have

skipped the dessert), and two bottles of Tikves Alexandria white wine. The

total bill, with tip, came to around £20. Half of that was the wine! We

finished off the second bottle slowly, before setting off for the café we

visited earlier in the day.

The cul-de-sac looked a lot more sinister

in the darkness, but as we ventured in our eyes adjusted to the darkness that

was only lightly dusted with moonlight from up above. We crept in to the

courtyard, half expecting the atmosphere to be a bit livelier for an evening,

so were disappointed to see only a handful of patrons. We sat towards the main

building at the back - in a corner and opposite another couple 10 feet away.

Our order for beer spoken in English piqued the curiosity of the other patrons,

but that soon abated. Over the course of two beers, we either discussed plans

for the rest of the holiday or fell into a relaxed silence, observing others in

the vicinity. By 1am we grew tired again, so paid our bill and departed back to

the apartment.